The U.S. is rapidly approaching the date at which its government can no longer pay for all federal obligations – also known as the ‘X-date.’ United States Secretary of the Treasury Dr. Janet Yellen has warned U.S. Congress that X-date could arrive as soon as June 1st.

Global attention towards the issue is rapidly accelerating. Markets are already pricing in political brinkmanship related to the possibility of the U.S. defaulting on its debt, and finance leaders of the G7 have engaged in discussions regarding increasing global economic uncertainty due to the impending crisis.

When the U.S. sneezes, the world catches a cold. The team at Nexus APAC have compiled an analysis of the 2023 U.S. Debt Ceiling Crisis including its impact on Australian Business, whether a default eventuates or not.

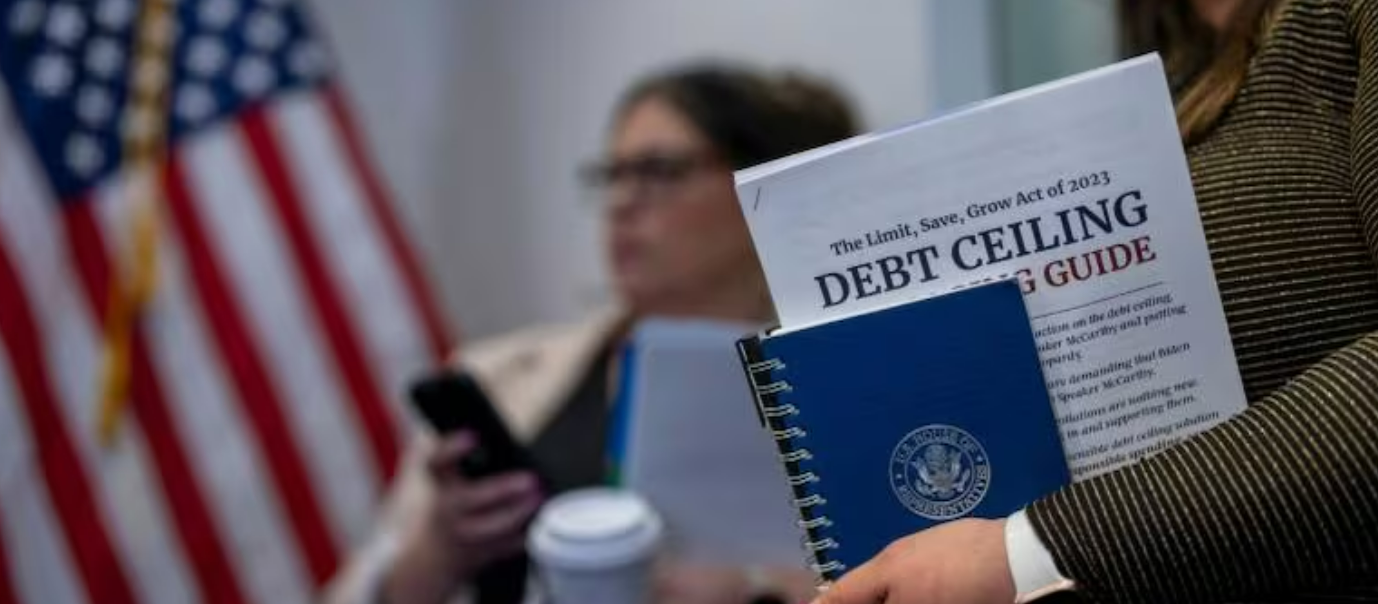

The Debt Ceiling Debacle

In the U.S., the debt ceiling is a legislative curb on the amount of national debt that the United States Department of the Treasury can incur. The Treasury sells bonds to pay for its mandatory and discretionary spending. Those bonds also formulate a basis for other parts of the global economy, from mortgage rates to foreign currency trade.

The U.S. debt ceiling is currently $31.4 trillion USD ($46.8 trillion AUD) – the U.S. hit that ceiling on January 19, 2023.

Immediately, the Treasury resorted to ‘extraordinary measures’ to finance expenditures without breaching the ceiling. The Treasury declared a ‘Debt Issuance Suspension Period’ for the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund, as well as the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund, allowing the agency to suspend new investments.

However, these accounting manoeuvres are only temporarily viable. If the Treasury exhausts its extraordinary measures, Congress has two options – it may either act to lift the ceiling or default on its debt obligations.

Should Congress default, or disallow further debt, the Treasury would not be legally permitted to sell any more bonds, and therefore would not have the resources to pay interest on government securities when due.

Why Now? The Relationship between the Crisis and U.S. Party Politics

At present, the U.S. has a divided government. President Joe Biden, a Democrat, controls the White House. The Democratic Party controls one-half of Congress – the Senate. As at the 2022 Midterm election, the Republican Party controls the other half, the House.

Although Republicans are a minority in the Senate, they threatened to use the filibuster for the first time in American history to stop the government from raising the debt ceiling.

Republican Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy is in a bind with hardliners in his party, who are calling for a balanced budget before they approve a debt ceiling rise. The U.S.’s last Budget Surplus occurred in 2001, the year former Democratic President Bill Clinton left office.

On April 17, 2023, Speaker McCarthy said that the Republican-controlled House is open to a deal to lift the debt ceiling into the next year (putting it squarely into the 2024 Presidential Election), but with a trade-off – Democrats would have to agree to freeze spending at 2022 levels, recoup tens of billions of dollars of unspent COVID-19 relief funds, and impose a 1% cap on future non-defence spending each year for a decade – amongst other conditions. It’s reported that Republicans also want to roll back student loan forgiveness and rescind President Biden’s climate change policies passed in last year’s Inflation Reduction Act.

President Biden has said he is optimistic that a deal could be reached before X-date. Speaker McCarthy continues to downplay the odds of success to increase the likelihood of extracting further concessions from the Democrats.

Ramifications for the Economy – From the U.S., to Australia, and Beyond

Since the debt ceiling was legislated in 1917, the U.S. Treasury has never exhausted its extraordinary measures. Thus, economists are facing unchartered territory in predicting the scale of damage caused by a U.S. debt default.

Many economists believe that a default would trigger an immediate recession. In a simulated debt ceiling breach, the Council of Economic Advisers predicted that the first full quarter after a default would see the stock market plummet by 45% and unemployment increase by 5 percentage points.

Investors such as pension funds and banks holding U.S. debt could fail. Interest rates would skyrocket. Tens of millions of Americans who rely on government support, including 60 million elderly Americans on Social Security, would suffer.

Moreover, because the U.S. government would be unable to enact counter-cyclical measures in this recession, there would be little support to help buffer the impact on American households and businesses, whose ability to offset by borrowing through the private sector would also be compromised.

Experts say a U.S. default could devastate global financial markets. Trillions of dollars globally are tied to the value of U.S. bonds, widely regarded as some of the world’s safest assets. If the value of those bonds were driven down, Australian reserves would be hurt. When U.S. yields increase, Australian yields would likely follow. If U.S. equity markets crater, Australian equity markets would certainly feel the shock wave.

Confidence in U.S. Treasury securities has led to the U.S. Dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency. The global ascendency of the USD has become a political and economic weapon for the U.S. The uncertainty-inducing default would sharply weaken the dollar. As a result, low-income countries could slip into debt crises causing geopolitical instability, particularly in the Indo-Pacific, to rise.

Another consequence would be enhancing the position of China. While the Euro would likely replace the dollar as the world’s primary unit of account, the Chinese Renminbi (RMB) would move into second place. As it is, China has been working with other BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, and India) to accept the Yuan as a unit of account.

What’s the likelihood of a U.S. debt default?

Last Friday, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office warned that “if the debt limit remains unchanged, there is a significant risk that at some point in the first two weeks of June, the government will no longer be able to pay all of its obligations.”

During the U.S.’s last debt ceiling crisis in January 2013, the Republican-held House wanted former President Barack Obama to eliminate funding for his Affordable Care Act. Political brinkmanship ensued until the day before X-date when Republicans relented, and the debt ceiling was raised. Some experts are projecting a similar scenario this time around.

Whilst markets remain sanguine, they have begun to price in a small chance of a disastrous default. The implied probability has roughly doubled since late March to 4.3%, according to modelling by research provider MSCI.

Should Congress agree to raise the debt ceiling, the risk won’t necessarily vanish. American debt is predicted to grow dramatically over the next decade.

Early on Wednesday morning, President Biden postponed his trip to Australia as part of a Quad Leader’s Summit later this month. While committed to the continued strengthening of the Quad, President Biden has reiterated that the debt ceiling crisis is “the single most important thing that’s on the agenda” and will remain in the United States while negotiations on resolving the debt ceiling crisis continue.

Latest posts by Nexus APAC (see all)

- United Kingdom General Election 2024: An Overview - April 15, 2024

- Australian Voters Go to the Polls - February 26, 2024

- Secretaries of Federal Departments – An Overview - February 1, 2024